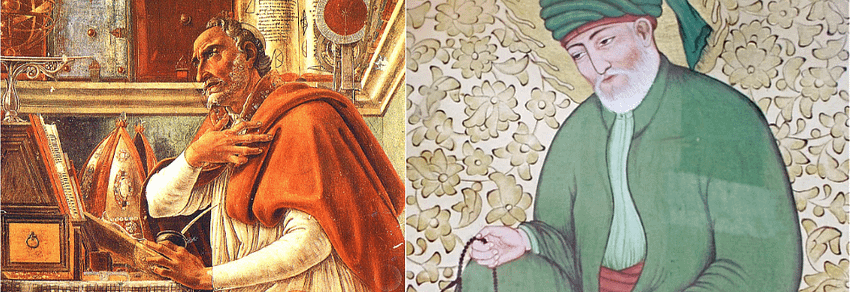

Rumi and Augustine both espouse a state of bliss achieved through oneness with the divine, yet their prescribed paths to attain this state are strikingly different. Rumi draws upon Sufi mystic traditions, emphasizing the importance of indulging in dance and music to lose oneself in devotion, thereby incorporating the body into the process of spiritual transformation. Augustine, on the other hand, seeks solace in getting closer to God by focusing on the soul and distancing oneself from bodily practices, which he feels create temptations and drive the soul away from salvation. While both share a common end goal, they diverge completely in their approach toward the use of practices such as dance and music in the journey towards attaining a blissful state of mind in their respective religious traditions.

Both philosophers grappled with why unity with God does not exist in daily life. However, they arrived at very different reasons, which shaped the ways they prescribed to seek union with the Creator. Augustine’s sense of separation from the divine is rooted in his belief that he is a sinful and flawed individual: “I went my way, farther and farther from you, proud in my distress and restless in fatigue, sowing more and more seeds whose only crop was grief” (Pine-Coffin 44). He feels unworthy of God’s love and unable to live up to the standards of morality and righteousness expected by God. Augustine spent a lot of time struggling to articulate the path to overcoming this feeling of unworthiness and being accepted by God. Rumi, on the other hand, did not anchor on sin as the source of unhappiness. He argued that, like a lover pining to be in the arms of their beloved, the human soul feels a sense of separation from the divine:

“How can I, heartlorn lover, get my discomfited fill?

My dropsied heart drinks gulps of blood

my eyes are ever wet and filled with tears” (Lewis 69).

Just as a lover can sing and dance their way to the heart of their soulmate, so can seekers of blissful union with God. True happiness comes from being with the one you love:

“We hear them from beyond sing melodies

of faith: “Here is your path, this way release.”

This is how we escape the confining cage” (Lewis 11).

Rumi asked his fellow devotees to indulge in physical experiences as an expression of their senses and revel in the joys of getting closer to the divine. Augustine had a groundbreaking realization that God did not create a specific entity like evil, but rather that evil was the absence of God: “We turned to you, and light was made…once we were in darkness, but now, in the Lord, we are all daylight” (Pine-Coffin 319). Just as darkness is not a constant state but merely the absence of light, Augustine preached a way of life that avoided anything that would take a worshipper away from God. The divine was the light that would dispel the darkness of sin and evil from life.

Rumi and Augustine’s divergent thoughts on the causes of a sense of separation from God are reflected in their significantly different views on the role of bodily actions such as dancing as a means to attain a sense of union with the Creator. In Sufi tradition, the practice of whirling and dancing is believed to induce a trance-like state that allows the devotee to connect with the divine. Rumi frequently alludes to this practice in his poetry, using dance as a metaphor for spiritual surrender and self-transcendence: “They free themselves from their own clutches when they can leap right out of their own flaws: they clap their hands and then they do a dance” (Lewis 40). Augustine, however, was concerned that self-indulgent practices like performing plays (including dancing) were diluting the path of the righteous. Recalling the wasted years of his youth, Augustine says, “We loved the idle pastimes of the stage and in self-indulgence we were unrestrained” (Pine-Coffin 71). Augustine believes that restraining the body is key to restraining the soul. Rumi, on the other hand, makes the connection to physical movement as a symbol of ecstatic devotion. This movement can lead to freedom from wants and desires and the resulting pain. He sees people as being trapped in their own clutches arising out of flaws. All humans have flaws, but by engaging in the physical activity of dancing while enveloped by thoughts of God, they can escape the clutches of suffering. Augustine, on the other hand, argues that the path to seeking bliss comes from an inward focus on the soul centered around thoughtful meditation, practice of the liturgy, and staying away from sensual experiences that might lead to self-indulgence.

The power of music as a tool to evoke deep emotions was recognized by Rumi as well as Augustine. However, they differed in their feelings about how music can be used in religious practice. Augustine was afraid that singing and harmony could also be used for entertainment and distract churchgoers from spiritual pursuits. He believed scripture set to tune should only serve the purpose of enhancing the text and aiding commoners in understanding the religious text: “I am inclined to approve of the custom of singing in church, in order that by indulging the ears weaker spirits may be inspired with feelings of devotion” (Pine-Coffin 239). However, he immediately cautions against letting music take over the emotions as it could be “far more moving than the truth which it conveys” (Pine-Coffin 239). Augustine advised against using music to the extent that it becomes gratifying for the senses as this would lead the mind astray and away from meditation. If such a thing were to happen, he would prefer not to even hear the musician. In stark contrast, Rumi deeply believed that music was at the heart of a spiritual experience. He often used melody and musical instruments as metaphors for journeys of the spirit. A devotee playing a tune through a reed appears to Rumi to be making a connection between the soul and the creator:

“Fire, not breath, makes music through that the reed –

Let all who lack that fire be blow away!

What races through the reed is love’s own fire” (Lewis 34).

As a deeply spiritual experience, Rumi feels that it is not the breath of the flute player that produces the music, but rather the inner fire driving the musician. The reed flute is simply a medium for the music that arises from the musician’s heart. He sees soulful music as moving not only the player but also the non-believers. The force is so strong that it causes anyone who listens to have their heart moved towards the divine.

While Augustine and Rumi differed in their ideas about the feeling of hunger, Rumi’s poem on fasting provides an interesting example of the confluence of their thoughts. Augustine holds fasting in high regard as a means of self-cleansing and a way to feel closer to God: “There is another evil which we meet with day by day …we repair the daily wastage of our bodies by eating drinking…I fight against it, for fear of becoming its captive. Every day I wage war upon it by fasting” (Pine-Coffin 234-235). Rumi also praises the exact same experience of fasting to achieve oneness with the divine:

“If the fast is hard,

yet it has a hundred charms

It has a certain sweetness

the low blood sugar of the fast” (Lewis 14).

Augustine focuses on the feeling of hunger as a step in the journey of redemption from sins. He uses it as a tool to suppress other sinful thoughts. Rumi takes the same feeling and focuses on the sweetness of the sensual experience—two very different narratives of a singular experience aimed at the same outcome.

Rumi and Augustine both believed that a sense of purpose in earthly life could come through the feeling of the soul uniting with the divine, a state where the boundaries between the soul of the individual and their creator are erased. In Masnavi Book 3: 4658-63, Rumi talks about the need to be one with God by fading into eternity: “When God appears, the seeker fades away” (Lewis 117). Rumi felt that the quest for fulfillment in life requires the believer to erase the boundary between the physical and the spiritual world. In Book X, Chapter 27, St. Augustine aspires to unite with the divine by being surrounded by the love of God: “You shone upon me; your radiance enveloped me … I am inflamed with your love” (Pine-Coffin 232). He echoes a sense of being surrounded by the presence of God and losing oneself in that state. Both thinkers emphasized the importance of self-awareness, continuous reflection, and a willingness to “give in” to God as key milestones in the journey to redemption.

The writings of both Rumi and Augustine were widely read and adopted by the followers of their respective sects of Sufi Islam and the Catholic church. The impact of their thinking can still be felt and seen today among the practices of the worshippers. Dance, music, and singing are interwoven into the religious practices of Islam. A more contemplative, silent, and inward-focused atmosphere is present in many Catholic churches. As different as they are, we must remember that both paths lead towards a feeling of unity with the Creator and a sense of fulfillment. This is what brings inner peace to human beings. Irrespective of the practices, appreciating and understanding the philosophy of Rumi and Augustine can lead humanity towards a more tolerant coexistence.

Works Cited

Augustine. Confessions. Translated by R. S. Pine-Coffin, Penguin Classics, 1961.

Lewis, Franklin. Rumi: Swallowing the Sun. Oneworld Publications, 2008.

(*Thanks to Prof. Mann for the recommendation to include an analysis of this poem)